If peak-era Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi had scored twenty goals within a time frame of six League games and little over three weeks, the football world would have raised its collective hands to applaud their genius. When little-known Romanian striker Rodion Camataru actually, not hypothetically, performed this cartoonishly unlikely feat back in 1987, all the footballing world managed to raise was a collective eyebrow and a number of influential voices in dissent.

If peak-era Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi had scored twenty goals within a time frame of six League games and little over three weeks, the football world would have raised its collective hands to applaud their genius. When little-known Romanian striker Rodion Camataru actually, not hypothetically, performed this cartoonishly unlikely feat back in 1987, all the footballing world managed to raise was a collective eyebrow and a number of influential voices in dissent.

Loudest among them was Austrian striker Toni Polster whose 39 goals for Austria Vienna had looked set to win him that season’s European Golden Boot title, this until Camataru’s late burst. Controversially relegated to the Silver Boot award, when Polster stated he would refuse to attend the ceremony (“I do not believe I can honestly shake his hand as a sportsman,”) he was expressing a view many across Europe concurred with. Even the Romanian sports daily Sportul seemed slightly embarrassed by the success and their coverage of the story was minimal, tucked away near the bottom of an inside page.

With no smoking gun to prove definitively that games were rigged to allow Camataru to score at will, people close to Dinamo suggested that western suspicion represented nothing more than a churlish unwillingness to recognise an extraordinary feat by the forward. His 44 goal total for the season was hardly an outlandish figure compared to other recent Golden Boot winners after all, and Dinamo Bucharest forwards had historically competed strongly for this award anyway: Dudu Georgescu (twice) and Dorin Mateut also won the Golden Boot between 1975 and 1989.

Television footage doesn’t exist to prove accommodating defending or not, but we do know that traditionally the most common route to fix results comes from questionable penalty awards. Just one of Camataru’s 20 goals came from the spot. And while not a well-known striker in the west, Camataru was in no way a talentless plodder who just happened to have good connections within the regime. This was a player known for his pace, strength and balance: a regular international striker who won 75 caps and led the line for his country at the 1984 European Championships. Domestically he was a two-time League champion with Universitea Craiova who refused to heed calls from the capital for years before finally transferring to Dinamo in 1986 only when they dangled the compelling incentive of a move abroad once he had completed three years with them.

What seemed to rankle was not the number of goals Camataru scored in total, rather the suspicious pattern in which they were accrued at a time when the number of goals needed to win the Golden Boot was calculable. By the final day of May, Camataru’s debut season with Dinamo had yielded a respectable 24 goals in 28 games. By the time the last round of fixtures had been played and the season completed on the 25th of June, that total had rocketed to 44. At no other stage of his lengthy career did Camataru manage better than 23 goals in a season, and yet now he suddenly scored almost that number during this controversial month alone.

Granting his achievement any benefit of the doubt would have been an enormous leap of faith considering the toxically corrupt environment in which it took place. By the second half of the 1980s organised football in Romania had deteriorated into a sham run for the benefit of a trio of the capital’s clubs. Steaua with its army and Ceaucescu connections sat on top, won almost all the trophies and embarked upon a 104 game domestic unbeaten run. The team of the secret police, Dinamo, sat next in the hierarchy and had to make do with perennial runners-up status in both League and Romanian Cup. Third in the pecking order was Victoria Bucharest, a tiny club that functioned as something akin to a Dinamo reserve side and had emerged from nowhere solely because of the influence their police connections brought.

That 1986-87 season was taking familiar shape with Steaua leading Divizia A ahead of Dinamo and Victoria. Camataru’s season started strongly with 17 goals in 17 games before his scoring rate slowed with just two added over his next 8 appearances. The turning point seemed to be the derby against Steaua in mid-May with Camataru putting in a subdued performance and failing to score in the 1-1 draw. With Steaua nine points ahead and Victoria six points behind, Dinamo’s League campaign was essentially over with an almost certain guarantee of another second place finish. And then came the deluge.

Those last six League games yielded 21 goals for Dinamo Bucharest with Camataru accounting for 20 of them. He scored a hat-trick as a minimum in five of those games and a mere double in the other. A consistent goal every other game forward throughout his career had suddenly metamorphosed into a 3.5 goal per game super-striker.

Another curiosity was how the goals benefitted Camataru individually but not Dinamo Bucharest collectively. Those half-dozen free-scoring games accrued just 4 points and fuelled suspicion there was an under the counter trade going on – Dinamo going easy on opponents on the understanding that those opponents went easy on Camataru in return.

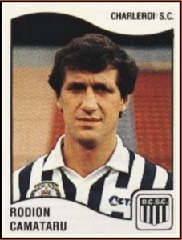

One further fixture offered Camataru the opportunity to prove there was genuine validity to his rich vein of form. The Romanian Cup Final pitched Dinamo up against, inevitably, Steaua and the army side, just as inevitably, won 1-0 with Camataru barely touching the ball. He played at Dinamo for two further seasons and scored a more conventional total of 32 League goals between them, before Dinamo honoured their promise to allow him to move abroad at the age of 31 for spells with Charleroi and Heerenveen.

Which leaves only the reason why so much effort was made to secure an individual award that was at best of passing interest to the European game. The most likely explanation was that helping a Dinamo player to win the Golden Boot was crumbs from the master’s table – a sop to the club for quietly playing along with their restricted role as always the bridesmaids, never the bride when proper honours were up for grabs.

The sheer weight of anecdotal evidence made it impossible to construct any argument against Camataru’s success being anything but a fabricated one, a position that did not take too long to be verified. Three years later after the collapse of the Ceausescu regime, the Romanian Sports Minister confirmed the inevitable truth. Valentin Ceausescu, son of the dictator and Steaua president made the arrangments to trade defeats in exchange for easy goals for Camataru.

UEFA acted with unusual haste at the time by withdrawing the Golden Boot and leaving it out in the cold for the next decade. When it did return the format was much changed and introduced a weighting system so that goals scored in a major Leagues were given more value than equivalents scored in fringe Leagues. UEFA also belatedly and retrospectively awarded Toni Polster his Golden Boot twenty years after the event.

Ironically the victim in this whole sordid affair is Rodion Camataru himself. Romanian footballers were little more than pawns on a giant political chessboard and in later years he spoke out about how he knew nothing of any arrangment: “All I know is I scored those goals, and that nobody stood by to let me put the ball in the net. I was never officially accused of anything, and was never asked to give back the trophy. Besides, why does nobody ask how Polster managed 39 goals?” He was the unwitting patsy; a good player artificially pushed into doing a short-term impersonation of a great one.

If he was questioning internally how easy goals seems to be coming for him during that freakish month, those questions had to be put in a broader context of a game where unusual events happened every week. Players became inured to the intricate web of corruption. Ultimately and most unfairly, Rodion Camataru became a touchstone for everything that was wrong with Romanian football in the dying years of the Ceaucescu regime.

Great piece.