Sepp Blatter didn’t seem to enjoy the climax of the 2012 Champions League Final very much. When asked to comment on the penalty shoot-out that decided the competition for Chelsea, Blatter could muster nothing more insightful than “tragic.” The now ex-FIFA President had an uncanny habit of never using a measured response when a simplistic overstatement was available, but a disregard for penalty shoot-outs as the best method of deciding deadlocked games is not solely the preserve of the most powerful bureaucrats in world football. Their perceived unfairness is aired as an issue after most high-profile shoot-outs and Blatter’s subsequent ramblings about how they compromise the spirit of the game is fairly typical of the criticism levelled against them.

Sepp Blatter didn’t seem to enjoy the climax of the 2012 Champions League Final very much. When asked to comment on the penalty shoot-out that decided the competition for Chelsea, Blatter could muster nothing more insightful than “tragic.” The now ex-FIFA President had an uncanny habit of never using a measured response when a simplistic overstatement was available, but a disregard for penalty shoot-outs as the best method of deciding deadlocked games is not solely the preserve of the most powerful bureaucrats in world football. Their perceived unfairness is aired as an issue after most high-profile shoot-outs and Blatter’s subsequent ramblings about how they compromise the spirit of the game is fairly typical of the criticism levelled against them.

With such criticism comes the rhetorical questions asking whether there must be a better way to decide important games, but there’s a good reason shoot-outs are still going strong after 42 years – basically no-one has come up with a better method yet. With no realistic or new alternatives on the table, attention turns to what we had before penalties, back to a time when tied games were decided on the toss of a coin.

With his important work in the upper echelons of the World Society of Friends of Suspenders, perhaps Mr Blatter was too busy to pay much attention to football during the 1960s. Had he been watching, surely not even the obstinate man that he is would argue that tossing a coin to decide a winner was a good advert for the game. Bill Shankly certainly didn’t think so. When Liverpool lost to Athletic Bilbao on the toss of a coin in the 1968-69 Fairs Cup, Shankly moaned that the collective administrative brains in Switzerland could surely devise some method where games were settled by events on the field. Admittedly, there is no record of him having expressed similar sentiments just a few years earlier when his Liverpool side overcame Köln via that same method.

When UEFA drew up its competition rules at the inception of the European Cup in 1955, the tossing of a coin – or a two-sided disc to be precise – as a method to decide ties was imagined as a last resort, a worst case outcome for when no standard method had succeeded in splitting teams. Back in those days there was no away-goals rule, so if the aggregate score was level after the home and away legs then a third match would be scheduled at a neutral ground instead. The assumption was that playing a potential maximum of five hours of football should produce a natural winner in most ties.

When UEFA drew up its competition rules at the inception of the European Cup in 1955, the tossing of a coin – or a two-sided disc to be precise – as a method to decide ties was imagined as a last resort, a worst case outcome for when no standard method had succeeded in splitting teams. Back in those days there was no away-goals rule, so if the aggregate score was level after the home and away legs then a third match would be scheduled at a neutral ground instead. The assumption was that playing a potential maximum of five hours of football should produce a natural winner in most ties.

UEFA was right, mostly it did. With even Real Madrid needing a couple of play-offs en route to their first five European Cup wins, this third match would become commonplace and mostly proved decisive in producing a tie winner. Many European Leagues were still part-time and amateur in these early days and this meant fatigue could often play a major part by the time a third game was played. In the first eight years of European competition, only once was a coin toss needed and even that instance might have been averted. The play-off between Wismut Karl Marx Stadt and Gwardia Warsaw in the 1957-58 European Cup was abandoned part way through extra-time because of floodlight failure. The scores were level at the time, so it was decided just to toss a coin to decide the winners. The East German side was successful in this, the first of the 21 European ties that would be decided using this method over the next dozen years.

While play-offs were useful for averting the need for games to be decided by the toss of a coin, their existence brought other issues and Napoli’s Cup Winners’ Cup campaign from 1962-63 is a case in point. Each of their three ties against Bangor City, Újpest Dózsa and OFK Belgrade ended deadlocked after the home and away legs, so each needed a play-off to produce a winner. The Italians had to add London, Lausanne and Marseille to their extended travel schedule: an itinerary that was great for sight-seeing but poor for stamina and travel costs. It was probably a relief to finally exit the competition when they lost their third play-off to the Yugoslavs. With Napoli playing nine matches in seven countries over just three rounds of the competition, the problem was apparent. Play-offs were becoming less and less economically viable for clubs and the disruption to the schedules they caused meant they were increasingly at odds with UEFA’s goal of standardising fixture dates across European competition.

Professionalism took a greater hold across the continent as the decade progressed with fitness and organisation improving considerably in the lesser Leagues. Games in European competition became less of a mismatch as smaller clubs became more resourceful at containing stronger ones. The situation was subtly shifting and now more ties needed a play-off, with, increasingly these play-offs failing to produce a winner. It made the system seem even more archaic – why go through the logistical difficulties of organising a third game when often you have to settle it anyway with the randomness of a coin-toss? If games were to be decided by chance, why not do that after the second match instead?

Professionalism took a greater hold across the continent as the decade progressed with fitness and organisation improving considerably in the lesser Leagues. Games in European competition became less of a mismatch as smaller clubs became more resourceful at containing stronger ones. The situation was subtly shifting and now more ties needed a play-off, with, increasingly these play-offs failing to produce a winner. It made the system seem even more archaic – why go through the logistical difficulties of organising a third game when often you have to settle it anyway with the randomness of a coin-toss? If games were to be decided by chance, why not do that after the second match instead?

The 1964-65 European Cup campaign was notably affected with three ties needing the dreaded coin-toss to decide the outcome. Liverpool’s aforementioned win over the West German champions Köln came in a Quarter Final tie and the random element involved seemed to jar even more in this instance. While it was a wholly unsatisfactory way to be eliminated at any stage of a competition, the effect seemed to be magnified in the latter rounds with the losing team having worked hard to get through to this stage in the first place,.

At the time the Inter-City Fairs Cup existed outside the auspices of UEFA and had its own committee, headed by Stanley Rous. It was this committee that pioneered the cancellation of the unloved play-off and introduced the away-goals rule to their competition. UEFA tentatively followed their lead and trialled the new format in the Cup Winners’ Cup – the European Cup would only follow suit a season later.

The law of unintended consequences was apparent though. The away-goals rule immediately proved a useful and easy to understand tool for producing clear-cut winners of ties level on aggregate. All fine, but it wasn’t exactly unusual for teams to win 1-0 at home and lose 0-1 away, or indeed produce some other combination of mirrored scores. Such combinations were outside the remit of the new rule to settle, so now, without the play-off, teams only had three and a half hours of football rather than five to produce a winner. The new rules had only resolved part of the problem. The number of matches that went all the way to needing a coin-toss to decide them was reduced, but, for the ones that did then the coin-toss came into play earlier. Three ties in the 1965-66 season and four ties the following year needed a toss to decide them which represented an undesirable upward trend.

Whilst the 1967-68 season was better from a club perspective, the problem was demonstrated instead in the international arena. The European Nations Cup was a much smaller competition back in those days and the tournament element consisted of just two semi-finals, a third place match and the Final. The hosts Italy and the Soviet Union played out a goalless semi-final in Naples and with the Final scheduled to be played just 3 days later, there was no scope to fit in a replay. Without any other mechanism for deciding the game, the dreaded coin-toss had to be brought into play. The Soviet captain Shesternyov guessed wrongly and Italy went through to the Final in the most underwhelming manner. A few months later, Israel similarly lost an Olympic Quarter-Final match by the drawing of lots. That defeat encouraged one of their officials, Yosef Dagan, to formulate a plan for the penalty shoot-out that would be put forward to FIFA. A solution couldn’t come quickly enough: the following season saw five Fairs Cup ties settled with coin-tosses – the most yet in any single season.

Whilst the 1967-68 season was better from a club perspective, the problem was demonstrated instead in the international arena. The European Nations Cup was a much smaller competition back in those days and the tournament element consisted of just two semi-finals, a third place match and the Final. The hosts Italy and the Soviet Union played out a goalless semi-final in Naples and with the Final scheduled to be played just 3 days later, there was no scope to fit in a replay. Without any other mechanism for deciding the game, the dreaded coin-toss had to be brought into play. The Soviet captain Shesternyov guessed wrongly and Italy went through to the Final in the most underwhelming manner. A few months later, Israel similarly lost an Olympic Quarter-Final match by the drawing of lots. That defeat encouraged one of their officials, Yosef Dagan, to formulate a plan for the penalty shoot-out that would be put forward to FIFA. A solution couldn’t come quickly enough: the following season saw five Fairs Cup ties settled with coin-tosses – the most yet in any single season.

Tossing the coin to settle a match would go out with the sixties and out with Benfica and Roma, the last two sides unfortunate enough to suffer from this most unsatisfactory of exits. The penalty shoot-out was approved by FIFA in June of 1970 and was ready to debut in the following season’s European competitions. British teams would be among the first to experience the excitement and the controversy they could bring: Aberdeen losing 5-4 on penalties to Honvéd in the Cup Winners’ Cup and Everton eliminating Borussia Mönchengladbach 4-3 on kicks at Goodison in the European Cup.

Tossing the coin to settle a match would go out with the sixties and out with Benfica and Roma, the last two sides unfortunate enough to suffer from this most unsatisfactory of exits. The penalty shoot-out was approved by FIFA in June of 1970 and was ready to debut in the following season’s European competitions. British teams would be among the first to experience the excitement and the controversy they could bring: Aberdeen losing 5-4 on penalties to Honvéd in the Cup Winners’ Cup and Everton eliminating Borussia Mönchengladbach 4-3 on kicks at Goodison in the European Cup.

We even had the first controversial talking point when the West German side complained bitterly that Everton keeper Andrew Rankin had been two yards off his line when he saved Ludwig Müller’s final kick. Everton manager Harry Catterick was far from convinced, even in victory: “I still say these penalties to decide a match are like a circus, but I can’t think of a better answer apart from a third game.”

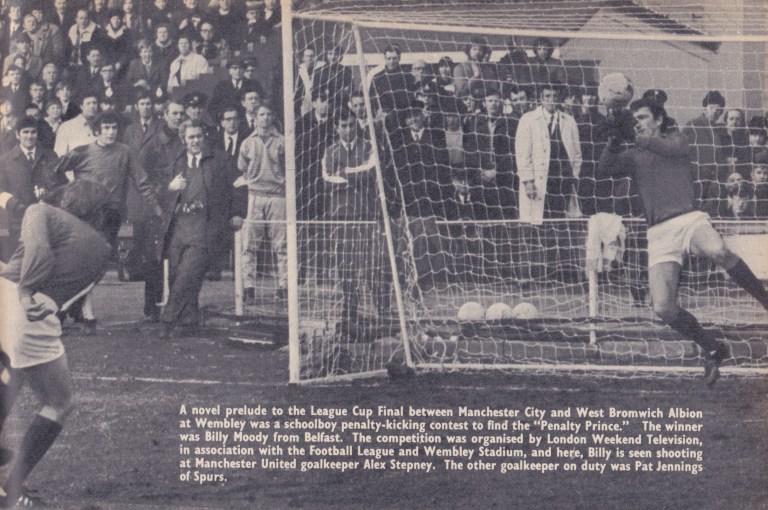

While this radical new system was summarily dismissed by some, for the majority it was thought of as something of a novelty and seemed to capture the imagination of the footballing public at large. The British media ran a number of pieces about penalty shoot-outs and how best to take them. Television cameras in London filmed Eusébio taking ten penalties against England keeper Gordon Banks. The Portuguese legend scored nine of them with exactly the same technique for each kick – shooting low and hard to the same spot just inside the post. QPR midfielder Terry Venables had a career record of 17 successful kicks from 17 attempts and he wrote an article for The Daily Mirror explaining to their readership the secrets of the art of penalty taking. In his first game after the article was published, Venables took a penalty against Cardiff and missed it.

To be successful in a penalty shoot-out a team needs nerve, skill and a bit of luck. To be successful in a coin-toss a team needs only luck. The next time you hear someone complain about the injustices of a penalty shoot-out defeat, ask if they would prefer we went back to using the toss of a coin to decide winners of deadlocked matches instead. It is of course probably not worth your while putting this ad hoc survey to supporters of the English national team for whom, surely, any off-the-wall alternative would be preferable to the ongoing tyranny of penalty shoot-out defeats.

We have a follow-up post called Calling The Toss which looks in more statistical depth at the European ties decided by the coin toss.

Great piece. Curiously, of course, it was the much-missed Watney Cup that was first to embrace the penalty shootout as far as English domestic football goes, with George Best the first player to score a shootout penalty and Denis Law the first to miss as Manchester United defeated Hull City in the 1970 competition.