Serial European Cup winners from the dim and distant past like Benfica and Ajax played a significant role in helping establish the competition as Europe’s premier club tournament, so it’s a sad indictment on the enormous changes we’ve seen over the past half century that these clubs will likely never reach the pinnacle of European football again.

We readily bemoan the changes in the Champions League-era that have brought such financial stratification to the game and cast many historic names from Europe’s smaller nations into the role of feeder clubs, but perhaps we do this without considering circumstantial factors that played a part in helping them to prosper in the first places.

While the bricks that built these successes were outstanding youth development, smart recruitment and visionary management, the cement that kept those structures in place was very much regulatory. These were very different times when players did not have EU-directed freedom of movement, freedom of contract under what we know as the Bosman ruling, nor freedom from the protectionist practices put in place by individual federations and national governments.

While we would applaud the undoubted progress the game has made in breaking down many of these barriers and improving the lot of the jobbing footballer, fans of Benfica or Celtic or Ajax will be somewhat conflicted to know that it was those very rules that allowed the greatest sides in their history to become competitive, and then stay at that level for extended periods without their talent being easily stripped from them by Europe’s wealthiest predators.

Two arbitrary bans put in place for the self-interest of the national federations of Spain and Italy had the inadvertent effect of changing the whole power balance of the European game. In 1962 the Spanish federation implemented a ban on its member clubs signing foreign players, then in 1966 its Italian counterparts followed suit. The bans were designed to diminish the cult of the foreign star and so force clubs to promote home-grown players, giving them more high-level playing time and thus ultimately benefiting the national teams.

These bans were seismic as both leagues relied heavily on foreign players for the success and prestige enjoyed by their major clubs – and many minor ones too. So too did the very federations seeking to change the laws as neither of them had shown any qualms about selecting oriundi, South American internationals playing in these countries Leagues and deemed to be selectable merely because of their current residency.

The bans were hugely unpopular in both countries and each and every year clubs lobbied hard to have them lifted. Part of this strategy involved lining up deals for big-name foreign stars they planned to acquire the following summer when the ban would, they hoped, be finally rescinded. Promising to bring in some of the world’s best footballers brought good propaganda to aid their cause – what official would want to be the one saying no to Pelé gracing Serie A or La Liga after all?

The relentless annual propaganda push didn’t work though and instead of big name stars there was only big time disappointment when the federations repeatedly extended the restrictions for yet another season. The status quo was only finally restored in Spain in 1973 and seven years later in Italy. But had those bans not been in place in the two richest and most acquisitive Leagues in Europe, or had at least been lifted a few years earlier, the footballing landscape during the 60s and 70s might have looked very different indeed.

Let’s start with Pelé, easily the world’s best and highest-profile player during this era. The oft-recanted story suggests that the Brazilian legend would never have been sold to Europe because of his designated national treasure status, but it’s a story that is at the very least more contestable than many think.

Real Madrid had put together what would have been a then world-record bid of £250,000 for his services just before the borders closed in Spain. Juventus entered serious negotiations in 1965 with a potential £500,000 deal on the table, bettered a couple of years later by Helenio Herrera’s Inter who claimed to have a potential £600,000+ deal in place were the ban to be lifted. These were astronomical sums in their days and Inter’s reported offer would have raised the world record transfer fee by 250%.

There was no other league in Europe wealthy enough to even think about affording Pelé, although in 1971 the newly formed Paris Saint-Germain club saw him as the sort of talisman who could bring enormous cachet to the new capital city club. Initial discussions suggested the cost would be far too onerous however and Pelé stayed in Brazil until his 1974 move to the the American NASL.

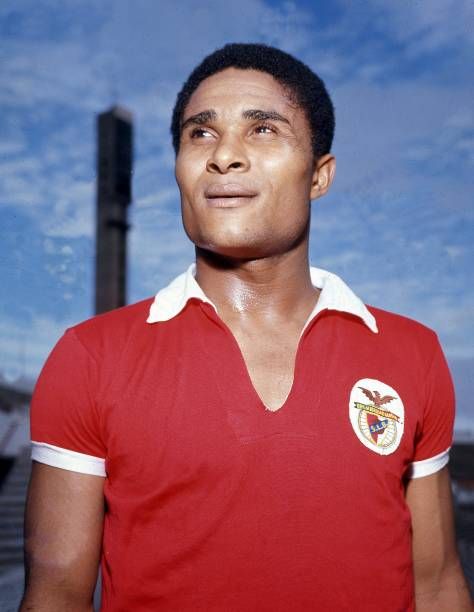

Benfica reached five European Cup finals during the 1960s and won the first two of them in 1961 and 1962. Their main scorer, inspiration and shining light for most of that golden era was Eusébio, and the Lisbon club’s successes would have been much diminished had either Juventus or Inter been able to complete the increasingly lucrative deals dangled in front of Benfica and the country’s military government for his services. Wary that the Italian borders might open to take away the main impediment to a deal being struck, Benfica even tried to sign the brilliant Levski Sofia forward Georgi Asparuhov as a potential replacement.

That transfer failed to materialise for a different forbidden reason – the one applied by communist governments to stop their stars moving legitimately to the west in their prime years, if at all. Even the fabulous wealth of Inter (again) was not enough to coerce Yugoslav officials into sanctioning a proposed £1 million move for Red Star Belgrade winger Dragan Džajíc. A similar scenario torpedoed an even wealthier projected deal Real Madrid were negotiating directly with Nicolae Ceaucescu for the talented Romanian playmaker Nicolae Dobrin in 1971.

Ajax’s wonderful total football sides of the early 1970s would have been unlikely to have won their trio of European Cups without the bans. Juventus was the first major club to attempt a deal for Johan Cruyff, though their interest cooled in favour of the potential acquisition of the Argentina Antonio Rattin instead. Barcelona first expressed interest in Cruyff in 1970 and it’s likely a deal would have been done there and then had the ban been lifted. From that same team Neeskens was wanted by Roma, while Wim Suurbier, Gerri Mühren and Piet Keizer all had lucrative deals awaiting them in Spain and Italy had circumstances permitted deals to be completed.

Instead the team stayed virtually intact and went on to enjoy the greatest era in their history, their many achievements committed to the record books in perpetuity by the time the foreigner ban was lifted in Spain in 1973. That autumn Cruyff finally moved to Barcelona for a world record fee. Neeskens joined him a year later while Gerrie Mühren and Johnny Rep followed in their footsteps to join Real Betis and Valencia respectively. One of the few young stars that Ajax held on to was Ruud Krol, at least until 1980 when the Italian borders re-opened and he swapped Amsterdam for Naples. Needless to say Ajax have not won a European Cup since.

The Dutch club’s dominance of the European Cup was followed by a similar three-season winning run by Bayern Munich, a sustained era of achievement unthinkable had Milan been able to complete their 1969 deal to sign Franz Beckenbauer. The rossoneri saw him as an ideal defensive partner for their other West German international, Karl-Heinz Schnellinger, who had arrived in Serie A before the ban was put in place.

When the federation announced that its focus was on the following season’s World Cup campaign in Mexico so the ban would stay in place, Milan president Franco Carraro sniffily announced his club would be perfectly happy to promote the promising young Italian Angelo Anquilletti instead. He went on to become a fine player and a full international, so things didn’t work out too badly for Milan in the end.

Thanks to a relentless drive to bring in as much commercial income as possible from tours and friendly games, Bayern Munich proved to be better capable of keeping rapacious Spanish predators away from their stars than Ajax, or their closest domestic rivals of the time, Borussia Mönchengladbach. Again, history could have been very different indeed if Barcelona had managed to tempt their first-choice foreign target Gerd Müller from Bayern in 1973. It’s hard to imagine the subsequent dominance of the tournament that the Munich club enjoyed without their unerringly prolific striker. Meanwhile Barcelona made do with their second-choice target, Johan Cruyff, and that worked out just fine for them.

The only valuable player that Bayern Munich did lose in this era was international full-back Paul Breitner who joined Real Madrid in 1974, and they coped well enough by winning a further two European Cups without his considerable presence. When their run at the pinnacle of the European game came to an end, the reasons were more organic with their team becoming stale, rather than their team being dismantled piece by piece as was the case across the border in the Netherlands.

This article has unabashedly explored an alternate and fictionalised world imagining what might have happened had Spain and Italy not chosen to emasculate their clubs at a time when they were by far the strongest in Europe. Some of the deals under discussion we have outlined might have happened, some of them might not have, but what is certain is that a substantial proportion of the world’s best talent would have continued to flow to the south of the continent had the borders remained open.

The European Cup was the exclusive preserve of the big southern European clubs from Madrid, Lisbon and Milan for its first decade, so it’s no coincidence that the bans weakened Spain and Italy and pushed the balance of power to the north of the continent for the first time after 1967. Over the competition’s long life that shift might have happened at some stage anyway, but it would not have likely been such a dramatic pivot. After Real Madrid won a sixth title in 1966, Spain had to wait 26 years to celebrate another. Following Inter’s retention of the title in 1965, only a single Italian success was recorded in the next two decades.

Scotland, England, the Netherlands and West Germany now provided first-time winners and the competition became the truly pan-European event that captured the imagination of clubs and fans from east to west its founders had hoped it would.

So while we are instinctively reticent to celebrate any of the murky restrictive practices that blighted the game’s history, we will raise a glass in tribute to those faceless, restrictive, petty and self-interested officials at the Spanish and Italian football federations. Without their blundering interventions, the whole, rich and compelling history of the European Cup, and the European football ideal generally, would be a very diminished thing.

Excellent article Craig, thank you.

Ajax won the Champions League in 1995 !!