Peruvian football has rarely been shy in looking abroad for inspiration and the helpful promptings of three nations in particular have played a major role in its development. The English came first: sailors introduced the game to Peru in the late nineteenth century, then Lima’s ex-pat residents helped drive its popularity by paying for the construction of a national stadium in Lima thirty years later.

Peruvian football has rarely been shy in looking abroad for inspiration and the helpful promptings of three nations in particular have played a major role in its development. The English came first: sailors introduced the game to Peru in the late nineteenth century, then Lima’s ex-pat residents helped drive its popularity by paying for the construction of a national stadium in Lima thirty years later.

The next step forward came courtesy of Hungary who, thanks to coach György Orth, properly organised the way Peru played the game for the first time. Orth had been an outstanding footballer in his day and had led a long and peripatetic management career before pitching up as the nation’s head coach in 1957. Before his arrival players of great natural talent had emerged, but rank amateurism in coaching and administration meant Peru muddled along for decades on the periphery of the South American game.

The next step forward came courtesy of Hungary who, thanks to coach György Orth, properly organised the way Peru played the game for the first time. Orth had been an outstanding footballer in his day and had led a long and peripatetic management career before pitching up as the nation’s head coach in 1957. Before his arrival players of great natural talent had emerged, but rank amateurism in coaching and administration meant Peru muddled along for decades on the periphery of the South American game.

Orth introduced his Hungarian methods and those initiatives helped the emergence of a rich seam of playing talent. Players like Óscar Gómez Sánchez, Vides Mosquera, Miguel Loyaza, Guillermo Delgado, Victor Benitez and the brilliant left-winger Juan Seminario put Peru firmly on the international map for the first time and attracted covetous glances from top clubs in Spain and Italy. This group of players featured as part of a fine national side that ran Brazil very close in qualification for the 1958 World Cup, and yet still Peru remained a nearly nation that had to go back to the inaugural 1930 tournament for its first – and only – participation on the world stage.

And so, finally, the Peruvian game would look towards the influence of Brazil to nudge them that final step forward towards the World Cup and international respect. The man they turned to was Waldyr Pereira, or Didi, as he was more commonly known. Didi was a double World Cup winner and one of the greatest players in the world during the 1950s and early 60s: an outstanding midfielder of grace and precision whose awareness of play, mastery of game management and quiet, assured leadership qualities marked him out for a future in management. He took coaching courses with Botafogo when his playing days ended and even in those formative years, it quickly became apparent that he had well-formed and quite distinct views on how the game should be played.

And so, finally, the Peruvian game would look towards the influence of Brazil to nudge them that final step forward towards the World Cup and international respect. The man they turned to was Waldyr Pereira, or Didi, as he was more commonly known. Didi was a double World Cup winner and one of the greatest players in the world during the 1950s and early 60s: an outstanding midfielder of grace and precision whose awareness of play, mastery of game management and quiet, assured leadership qualities marked him out for a future in management. He took coaching courses with Botafogo when his playing days ended and even in those formative years, it quickly became apparent that he had well-formed and quite distinct views on how the game should be played.

After a short and unsatisfying spell as an assistant coach with the Rio club, Didi realised his ambitions lay in different areas from most other coaches. What he sought was less a conventional coaching role and more of a project – a blank canvas for him to project his ideas upon. With his weighty playing reputation opening doors all over the continent, many were surprised when he accepted a role with the unfashionable Peruvian club Sporting Crystal in 1962. In what became a recurring theme throughout his managerial career, Didi’s primary motivation was controlling all the aspects of a club he felt he needed to be able to shape to realise his vision, rather than personal, financial enrichment.

This ambitious approach entailed a remit loftier than merely improving his new Sporting charges and their results. Didi’s project involved nothing less than a revolution in the way the game was approached, played and run throughout the country. The country’s football fraternity was mesmerised by him. As if having an all-time great of the game like Didi working within their borders wasn’t exciting enough, here was a man of integrity and belief who seemed to genuinely care about improving the nation’s footballing landscape. When he made a strong case for provincial champions participating in top division national football to strengthen competition, people listened and the Federation was happy to approve his suggested changes.

This ambitious approach entailed a remit loftier than merely improving his new Sporting charges and their results. Didi’s project involved nothing less than a revolution in the way the game was approached, played and run throughout the country. The country’s football fraternity was mesmerised by him. As if having an all-time great of the game like Didi working within their borders wasn’t exciting enough, here was a man of integrity and belief who seemed to genuinely care about improving the nation’s footballing landscape. When he made a strong case for provincial champions participating in top division national football to strengthen competition, people listened and the Federation was happy to approve his suggested changes.

Although Sporting finished League runners-up on both occasions, Didi’s initial two-year spell with the club was considered a success. His growing reputation drew offers back home but his return was a misjudged one. In Brazil, club Presidents barely allowed coaches to even pick teams without interference, yet alone get their hands on any of the other levers of power. Didi must have known there was no chance he would be given the degree of control he had enjoyed in Peru. It would be a period of disillusionment for him, finally broken when the call came from Sporting asking him to return in 1967. Didi picked up where he left off, Sporting became Peruvian champions the following year and the Brazilian had his first managerial honour.

With the 1970 World Cup looming, the Peruvian Federation was determined to build on the growing confidence in the domestic game and put together a genuinely competitive qualification campaign. To general consensus it was decided that an experienced foreign manager was necessary, but the sticking point was contracting a heavyweight coach with only featherweight wages on offer. The preferred choice was Adolfo Pedernera but negotiations broke down as soon as the Argentinian outlined his £1,500 monthly salary expectations.

Didi’s still-limited command of Spanish had been seen as a barrier to him being a contender for the post, but with Pedernera out of the picture attention turned back towards him. The Brazilian was interested in the role on the understanding that his involvement would come, as ever, with plenty of conditions. Reasoning that qualification would be impossible under the present set-up, he demanded numerous reforms to allow him to prepare as he felt necessary. A canny operator, in order to make his candidacy more compelling, Didi was smart enough to sugar coat his demands by offering to do the job in tandem with his Sporting Crystal role for no extra recompense beyond a bonus if he secured qualification. The Peruvian Federation agreed and had its heavyweight manager on the cheap. Didi had his new project, on his own terms and now he could go to work imposing his ideas on the best players in the country.

His footballing philosophy was one very much shaped by what he learnt as a player in Brazil and Spain. Going against the tactical conventions of the age held no fears for him and, true to his Brazilian roots, he insisted on a positive, attacking approach for his teams. His Spanish sojourn at Real Madrid and the observation of Alfredo Di Stefano’s perpetual motion had also taught him about the importance of physical fitness, continual movement and physical strength – qualities traditionally not particularly prized in Brazilian football.

Didi’s fascination with aspects of Italian football culture was harder to pin down. He had no playing affinity with a country whose main legacy to the game – the defensive straitjacket of catenaccio – was an anathema to his attacking convictions. It transpired that the Brazilian had taken great interest in the role that psychological conditioning had played in the success of Helenio Herrera’s Inter teams. The mind was a barely-explored area in football and there was limited appreciation of how confidence and morale impacted drastically on player performances. Didi wanted to master this science to counter what he perceived as the in-built inferiority complex of the typical Peruvian footballer.

Didi’s fascination with aspects of Italian football culture was harder to pin down. He had no playing affinity with a country whose main legacy to the game – the defensive straitjacket of catenaccio – was an anathema to his attacking convictions. It transpired that the Brazilian had taken great interest in the role that psychological conditioning had played in the success of Helenio Herrera’s Inter teams. The mind was a barely-explored area in football and there was limited appreciation of how confidence and morale impacted drastically on player performances. Didi wanted to master this science to counter what he perceived as the in-built inferiority complex of the typical Peruvian footballer.

Another Italian-inspired method that helped define his regime was the dreaded in ritiro – the practice of teams spending extended periods in isolated locations, away from friends and family, to improve focus and relationships between teammates. With player wages and bonuses to be paid in full by the Federation, Didi pushed through an agreement allowing him to take his national players into retreat in advance of all major games. Italian-style iron discipline was key to Didi’s approach too. The unspoken contract between club and player in Italy was a complex one: Serie A clubs paid lavish salaries but in return demanded an unprecedented level of control over the lives of their players. Concerned about the naturally lackadaisical manner of Peruvian footballers, Didi’s autocratic approach was, to his mind, the only way he could hope to drill them into the sort of disciplined unit he associated with European national teams.

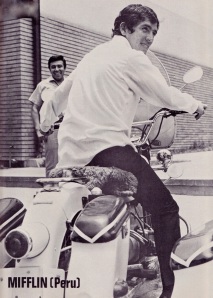

It was a bold and groundbreaking approach that no other coach had ever attempted in Peru. All smoking was banned in camp and Didi – a renowned chain-smoker himself – led by personal example and refrained too. His new, tougher and more professional approach to preparation wasn’t popular, but certainly appeared to inspire a greater esprit de corps in the squad. Subtle tactical changes were brought in to compensate for weaknesses: Peru’s defence was collectively slack at marking and poor in the air, so Didi made the inspired move to shift from a 433 to a 4123 formation and adapted midfielder Ramón Mifflin to play as a Beckenbauer-style sweeper.

It was a bold and groundbreaking approach that no other coach had ever attempted in Peru. All smoking was banned in camp and Didi – a renowned chain-smoker himself – led by personal example and refrained too. His new, tougher and more professional approach to preparation wasn’t popular, but certainly appeared to inspire a greater esprit de corps in the squad. Subtle tactical changes were brought in to compensate for weaknesses: Peru’s defence was collectively slack at marking and poor in the air, so Didi made the inspired move to shift from a 433 to a 4123 formation and adapted midfielder Ramón Mifflin to play as a Beckenbauer-style sweeper.

Competition for the single Mexico ’70 qualification place came from Bolivia and more ominously Argentina, the firm favourites to advance despite being a complacent team bereft of much attacking threat. The altitude of La Paz confounded opponents then as it does now and Bolivia defeated both Argentina and Peru, only to lose both returns as was the tradition. Peru sprung a shock with a 1-0 win in Lima over a bad-tempered, ten-man Argentine side and now needed only a draw in the Buenos Aires return to qualify.

Didi’s team selection for this crucial game was affected by suspensions resulting from the two dismissals in the contentious defeat in La Paz. With the lynchpin Mifflin unavailable, Didi boldly switched to a 424 formation and took the game to Argentina. It was a gamble that paid off handsomely as the pace and width of the Peruvian attack constantly unsettled the home side and silenced the 70,000 crowd. Peru twice led through Oswaldo Ramirez goals, twice Argentina levelled. The second equaliser came in the last-minute but didn’t unnerve the visitors who held out for the few remaining seconds to deservedly earn their point and their World Cup qualification.

Didi’s team selection for this crucial game was affected by suspensions resulting from the two dismissals in the contentious defeat in La Paz. With the lynchpin Mifflin unavailable, Didi boldly switched to a 424 formation and took the game to Argentina. It was a gamble that paid off handsomely as the pace and width of the Peruvian attack constantly unsettled the home side and silenced the 70,000 crowd. Peru twice led through Oswaldo Ramirez goals, twice Argentina levelled. The second equaliser came in the last-minute but didn’t unnerve the visitors who held out for the few remaining seconds to deservedly earn their point and their World Cup qualification.

Read Part Two of this story in which we look at how Didi’s side took on – and surprised – the world at the Mexico ’70 World Cup.