This fascinating article about the clash of Catholicism and Communism in 1950s Ireland played out through the prism of football comes care of writer Conor McCabe and is based on a paper he presented at the 2005 Irish Sport History Conference. This is an abridged version and is republished on BTLM with the author’s kind permission.

This fascinating article about the clash of Catholicism and Communism in 1950s Ireland played out through the prism of football comes care of writer Conor McCabe and is based on a paper he presented at the 2005 Irish Sport History Conference. This is an abridged version and is republished on BTLM with the author’s kind permission.

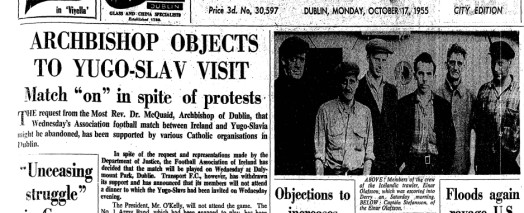

In 1955 the Irish political, cultural, and religious establishment found itself challenged by an unusual and reluctant opponent: The Football Association of Ireland (FAI). The clash arose over a friendly soccer game between the Republic of Ireland and Yugoslavia, which was played at Dalymount Park on 19 October of that year. The Catholic archbishop of Dublin, Dr. John Charles McQuaid, one of the dominant figures in Irish 20th century life, called for the cancellation of the game. This was echoed by various government ministers, senior civil servants, and Catholic lay organisations. The Irish national broadcasting service Radio Televis Éireann (RTE) declined to cover the game after its main sports commentator, Phil Greene, pulled out of the broadcast.

The protests arose out of the continued persecution of the Catholic Church in communist Yugoslavia, and were similar in tone to other protests held in Ireland over the previous seven years. The fact that the game went ahead with an attendance of around 21,400 has been read by some as a counter-protest against the forces of conservative Ireland, especially the public influence of archbishop McQuaid. Indeed, the archbishop’s biographer, John Cooney, wrote that the Yugoslavia game was ‘a populist revolt against McQuaid’s iron rule; the first of his reign.’

The controversy, however, reveals a clash between classes and culture in 1950s Ireland, rather than one between politics or ideology. This is not to say that 1950s Ireland was bereft of clashes over politics or ideology, but that the Ireland v Yugoslavia game became a protest against an attempt by the dominant Irish conservative forces to interfere with the most popular cultural activity of working class Dublin, rather than one energised by a desire on the part of the working class to confront the government, the Catholic Church, or the permanent secretaries of the Irish civil service. The game also provides an entry into Irish working class life – an area often neglected by Irish historians, and one with a culture that, on this occasion at least, found itself in uneasy conflict with the Irish establishment.

According to the Irish Press sports journalist, Sean Piondar, Yugoslavia was ‘perhaps the greatest football team – for skill, speed and combination – to visit Dalymount for many seasons [and] will be favourites to win well against Ireland.’ Since 1920 Yugoslavia had lost only 31 out of 184 games, and took silver at the 1948 Olympic Games. In 1954 they beat England in Belgrade, having drawn against them in London in 1950. Two of the Yugoslav players took part in an exhibition match in Windsor Park in Belfast on 13 August 1955. The match was Great Britain and Northern Ireland versus Europe XI. The game ended 4-1 for Europe, with Vukas from Yugoslavia scoring a hat-trick for the visitors in the first ten minutes. It was reported in the press that Yugoslavia intended to field a ‘stars only’ side for their game against Ireland, with both Vukas and Boskov from the Europe XI team confirmed for the fixture. ‘That form’ wrote the Irish Press, ‘is enough to attract a bumper audience.’ The Press went on to say that ‘win, lose or draw their first game with Yugoslavia, will Ireland have a return to Belgrade? Almost certainly – within the next two years.’

The Irish Press had every reason to predict a large crowd, as that was the norm for a game against quality, and expectant, opposition. Later that week a contributor to the Dublin-based periodical, Irish Soccer, wrote that Ireland ‘must try to model [its] play on that of the world’s most powerful teams. We must study the play of such masters of the game as Hungary, France and Yugoslavia. What better way to do this than to play matches against such opponents?’ The way to get stronger, the argument went, was to play against stronger teams. ‘One such match can teach more than fifty films or lectures’, the contributor wrote, while saying that if the game against Yugoslavia, which already was gaining controversy, was ‘supplemented by other such games, we will never again go into our international games wondering by how much we will be defeated.’ As it stood, Ireland’s record at international level was solid, as was the home attendance, which rose or fell according to the quality of opposition.

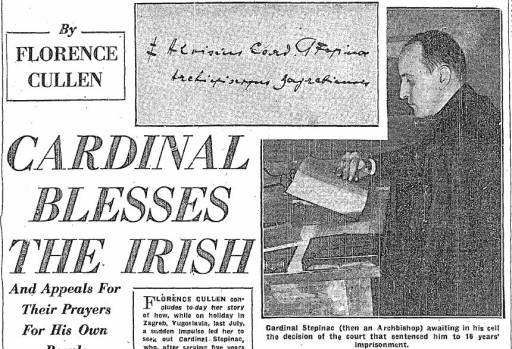

The issue at the heart of the controversy was the persecution of the Catholic Church in the Eastern Bloc, in particular, Yugoslavia and Hungary. Protests in Ireland came from the establishment, the trade union movement, and grassroots organisations. On 21 November 1946, James Dillon, a member of Dáil Éireann (the Irish national parliament), put a motion condemning the recent imprisonment by the Yugoslav authorities of the Archbishop of Zagreb and Primate of Croatia, Aloysius Stepinac. The Archbishop had been found guilty of high treason and war crimes, and sentenced to sixteen years. Dillon’s motion called ‘upon all Christian peoples and all those who do not actually hate Christendom to join in repudiating as fraudulent this pseudo-trial and in stigmatising it for what it is—a crude pantomime of justice…’ It went on to say that the purpose of the trial was to defame ‘Christianity in general and the Catholic Church in particular, so that the international Communist conspiracy against individual liberty everywhere may be relieved of its most formidable and uncompromising challenge, which must always come from Christianity’. The motion was rejected by the government in favour of less strongly worded appeal by the Prime Minister Eamonn de Valera, Taoiseach and Minister for External Affairs.

The motion also called on the Minister for External Affairs to pursue the case of Archbishop Stepinac through international diplomacy ‘and to take such other steps as may be proper to secure for them the adherence of freedom-loving peoples.’

The debate between the two motions, which both condemned the treatment of Cardinal Stepinac, focused greatly on the Catholic identity of the Irish Free State, and its articulation through its support for Archbishop Stepinac. Richard Mulcahy, the leader of the main opposition party, Fine Gael, said that a unanimous motion would ‘show to the people who despise and trample on the Catholic Faith in the world what the Catholic Faith means to us in the discharge of our public duties and responsibilities.’

The debate became one where the issue of condemning the treatment of Archbishop Stepinac was secondary to whether the opposition or the government was the more Catholic, even if the catholicity of the Taoiseach was above question.

The motion was praised by the Irish ambassador to the Holy See, Joseph Walshe, who wrote to Frederick Boland, assistant secretary of the Department of External Affairs, that ‘the Taoiseach had given a superb lead to the world.’ Representations were made by Irish diplomats to the British, Canadian, and US governments over the Stepinac case, and on 7 January 1947 the Pope sent a telegram and his blessings to the Irish government and people for a gesture which was ‘worthy of the noble traditions of Catholic Ireland.’

Irish protests against the treatment of Archbishop Stepinac were not confined to the Dáil. In February and March 1949, a series of masses were held across Ireland in support of Stepinac, as well as Cardinal József Mindszenty, Primate of Hungary. On 8 February, Mindszenty was sentenced to life imprisonment for treason against the Hungarian state. Almost immediately, mass notices appeared in the national and local newspapers.

The same year, over 40,000 people took part in a Mayday rally in support of the Catholic church in communist Europe, and in particular Archbishop Stepinac, who remained in Lepoglava prison for his collaboration with the Ustasha regime in Croatia during the second world war. The Mayday rally, the debates and motions of the Dáil, and the list of masses offered by a cross-section of Irish society, portray a society that saw the treatment of the Catholic Church in Yugoslavia and Hungary as nothing short of evil. They also show that in Ireland in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the names of Cardinal Mindszenty and Archbishop Stepinac needed little introduction.

In 1947 John Charles McQuaid wrote that ‘the case of Archbishop Stepinac is very complex and very simple.’ The complexity was Yugoslavia during the war, and the simplicity was ‘the directness of the supernatural ideal which guided the Archbishop [and which] allows us to understand his attitude in any position of crisis.’ His actions were guided by God, and because of this, ‘in his trial and unjust condemnation, therefore, Archbishop Stepinac is but another symbol of the unending persecution of the One, True Church.’ Archbishop Stepinac was a Croat nationalist who welcomed at first the establishment of the Nazi-backed Ustasha regime, but by 1942 had withdrawn his support for the regime, in particular for Ante Pavelic, the wartime dictator of fascist Croatia. Archbishop Stepinac’s arrest and subsequent imprisonment had more to do with the complexity of wartime Croatia than with the ‘simplicity’ of his spiritual guidance, but a priest behind bars in a communist country was never going to be seen in Ireland in terms other than of persecution – with Archbishop Stepinac a martyr, ‘rotting in a Bolshevik jail.’

In 1947 John Charles McQuaid wrote that ‘the case of Archbishop Stepinac is very complex and very simple.’ The complexity was Yugoslavia during the war, and the simplicity was ‘the directness of the supernatural ideal which guided the Archbishop [and which] allows us to understand his attitude in any position of crisis.’ His actions were guided by God, and because of this, ‘in his trial and unjust condemnation, therefore, Archbishop Stepinac is but another symbol of the unending persecution of the One, True Church.’ Archbishop Stepinac was a Croat nationalist who welcomed at first the establishment of the Nazi-backed Ustasha regime, but by 1942 had withdrawn his support for the regime, in particular for Ante Pavelic, the wartime dictator of fascist Croatia. Archbishop Stepinac’s arrest and subsequent imprisonment had more to do with the complexity of wartime Croatia than with the ‘simplicity’ of his spiritual guidance, but a priest behind bars in a communist country was never going to be seen in Ireland in terms other than of persecution – with Archbishop Stepinac a martyr, ‘rotting in a Bolshevik jail.’

The issue of Archbishop Stepinac was sufficiently strong in 1952 for the FAI to quietly decline Yugoslavia’s request for an international match, after the sporting body had consulted with Archbishop McQuaid. The FAI’s unofficial ban on playing Yugoslavia was out of step with the rest of the International soccer community, and by 1955 it felt that it could no longer decline Yugoslavia’s request to play against Ireland, and agreed to host the team in Dublin. It was a move welcomed, at first anyway, by the sports media and soccer fans. Unlike the previous occasion in 1952, however, this time FAI did not consult the Archbishop beforehand. McQuaid had no knowledge of the game until it was brought to his attention in the immediate days before the fixture. This was despite the large coverage the match had generated in the weeks leading up to the fixture. Soccer, it seems, did not figure on the Archbishops radar. The Archbishop’s ‘regret that the match had been arranged’ made the headlines, and into the history books, but opposition to this particular match, and to Yugoslavia, had already begun before the Archbishop made his views known to the FAI.

On Thursday 13 October the Irish Catholic, in an article headed “Tito’s footballers in Dublin”, reported that the Catholic Federation of Secondary Schools’ Union had protested ‘against the coming to Dublin of a team representing Yugoslavia.’ The same day the Department of Justice received a visa application, via telegram from London, for the Yugoslav football team who were due to arrive in London on Monday 17 October ‘en route to play Ireland at Dalymount on 19th October.’ The Department of Justice would later say that this telegram was the first that it knew about the Yugoslav game, although the Irish Press, again on Thursday 13 October, in an article titled ‘President to see Yugoslav match’, wrote that ‘the president [of Ireland] has informed Mr. J.L. Wickham, FAI secretary, of his intention to attend the soccer international against Yugoslavia in Dublin next Wednesday.’ The article, which appeared on the sports pages, also said that ‘in the Dalymount Park Council Box will be government ministers and other Dáil deputies and members of the Diplomatic Corps.’ At this stage at least, the match had all the appearance of official government support.

On Thursday 13 October the Irish Catholic, in an article headed “Tito’s footballers in Dublin”, reported that the Catholic Federation of Secondary Schools’ Union had protested ‘against the coming to Dublin of a team representing Yugoslavia.’ The same day the Department of Justice received a visa application, via telegram from London, for the Yugoslav football team who were due to arrive in London on Monday 17 October ‘en route to play Ireland at Dalymount on 19th October.’ The Department of Justice would later say that this telegram was the first that it knew about the Yugoslav game, although the Irish Press, again on Thursday 13 October, in an article titled ‘President to see Yugoslav match’, wrote that ‘the president [of Ireland] has informed Mr. J.L. Wickham, FAI secretary, of his intention to attend the soccer international against Yugoslavia in Dublin next Wednesday.’ The article, which appeared on the sports pages, also said that ‘in the Dalymount Park Council Box will be government ministers and other Dáil deputies and members of the Diplomatic Corps.’ At this stage at least, the match had all the appearance of official government support.

The Department of External Affairs, in particular its assistant secretary, Frederick Boland, had long witnessed the treatment of Archbishop Stepinac as a block to diplomatic relations between Ireland and Yugoslavia. In September 1950 an attempt was made by the Yugoslav authorities to appoint a Consul General de Carrière in Dublin. The Yugoslav ambassador in London was informed that ‘having regard to the public feeling occasioned here by events in Yugoslavia such as the trial and imprisonment of Archbishop Stepinac, the arrival of a Yugoslav representative in Dublin would be apt to cause disagreeable criticism and press comment to which they [the government] feel no official representative in this country should be exposed.’ In February 1953 a move was made within government to reduce as far as possible all purchases from communist countries. In a memorandum from the then Minister for Finance, Seán MacEntee, the point was made that ‘to the degree that non-communist countries do business with communist states… they may be said to be aiding in a greater or lesser degree the development of communist strength…’ The Minister went on to say that because of this he felt ‘bound to press for a total ban on trades with the countries at present under communist rule.’ At the highest level of government in Ireland in the early 1950s there was a robust opposition to trade links with communist countries, and diplomatic links with Yugoslavia, that was not without an ideological and religious element.. When Archbishop McQuaid made his request that the game be abandoned, in government circles at least he was pushing on an already open door.

The FAI held its special meeting at its offices on Merrion Square on Saturday 15 October and agreed, with one dissension, to proceed with the game. The chairman, Mr. S.R. Prole, said that they regarded the matter as a sporting affair between two countries, and that he was sure ‘that the counterpart of the FAI in Yugoslavia had as much say in the politics of that country as the association had here.’ Mr. Rapple, honorary secretary, called on the delegates to support the proposed game and made the point that ‘if it came to politics they might find that they did not agree with some of the things their own government did in Ireland.’ Mr. Clery said that the association was being put in the spot, and that ‘it would be a sorry day for this country when visiting players and officials would be asked their politics or religion.’ Mr. E.W. O’Connor said that he would have voted against the match had he been aware to the objections now raised, but, at this stage, it would be unreasonable to ask them ‘to accede to a request from the government or the Archbishop.’ The only vote against the hosting of the Yugoslav team came from Lt.-Col. T. Gunn of the Army Athletics Association, who said that the controversy had placed him in a very awkward position. ‘Without saying anything more’, he told the meeting, ‘I must oppose the proposal to go on with the match.’ Immediately after the meeting, Mr. Wickham received a call from Mr. Coyne who informed him that the government had decided to grant visas to the Yugoslav team and officials. He made it clear that the decision was made in light of the fact that arrangements for the game were already advanced, and of the ‘lateness of the time that representations were made to call it off.’ The FAI agreed to write to the Archbishop to explain the reasons behind the game.

The decision to grant visas, however, did not stop the government from making known its opposition to the game by withdrawing its official representation. The press was informed late on Saturday night that the Irish President ‘had found it necessary to cancel his acceptance of an invitation to attend the game.’ No government ministers attended the game, although Oscar Traynor greeted the players before kick-off in his capacity as FAI president. The FAI was informed that the no.1 Army Band would not be present on Wednesday to play the national anthems, while the management committee of Transport football Club said that, in light of the Archbishop’s objections, none of its officials would attend ‘either the match or the reception for officials afterwards.’ Similarly, Philip Greene, the RTE sports commentator, informed the press that in light of the Archbishop’s comments, he would not be available for the proposed radio commentary on Wednesday. Niall Tobin was due to open the coverage with a five-minute introductory talk in Irish. No replacement was found for Phil Greene, however, and the match was not covered by RTE.

The decision to grant visas, however, did not stop the government from making known its opposition to the game by withdrawing its official representation. The press was informed late on Saturday night that the Irish President ‘had found it necessary to cancel his acceptance of an invitation to attend the game.’ No government ministers attended the game, although Oscar Traynor greeted the players before kick-off in his capacity as FAI president. The FAI was informed that the no.1 Army Band would not be present on Wednesday to play the national anthems, while the management committee of Transport football Club said that, in light of the Archbishop’s objections, none of its officials would attend ‘either the match or the reception for officials afterwards.’ Similarly, Philip Greene, the RTE sports commentator, informed the press that in light of the Archbishop’s comments, he would not be available for the proposed radio commentary on Wednesday. Niall Tobin was due to open the coverage with a five-minute introductory talk in Irish. No replacement was found for Phil Greene, however, and the match was not covered by RTE.

The response from the Irish laity was robust. In a letter to the FAI, Mr. M.L. Burke, supreme secretary of the Knights of St. Columbus, wrote that ‘it is most regrettable that your association, in which so many tens of thousands of Irish Catholics are found, has failed to realise how distasteful to Irish Catholics is this link with a communist-dominated country.’ The secretary-general of the Guilds of Regnum Christi, Mr. M. O’Connell, told the press that his organisation supported the protests because the ‘communist government of Yugoslavia would make capital out of it in its struggle with the Catholic Church. The League of the Kingship of Christ released a statement on Sunday night which emphasised ‘the existence of a special bond of union between ourselves and our brothers who suffer behind the Iron Curtain, because they and we are members of one another in the mystical body of Christ’, and that charity demands that asylum should be granted to any player who so wished it. The president of An Rioghacht, Mr. Brian J. McCaffery, said that asylum should be offered to any player who wishes to remain in Ireland, while at the same time criticising the Department of Justice for the ‘amazing and absurd guarantee which has been forced on the Football Association of Ireland.’ This was in reference to the stipulation by the Department of Justice that the FAI should cover the living costs of any player who wished to seek asylum. The Catholic Association for International Relations wrote an open letter to the Yugoslav players, which stated that while’ our football association is a free, voluntary organisation of sportsmen, having no connection with the government…yours is under the control of a state department’, and that the bulk of the Irish people ‘are unhappy about your visit.’

The Yugoslav players arrived in Ireland shortly before midnight, Monday 17 October, having only recently heard about the controversy surrounding the game. The team was met at the airport by senior FAI officials, uniformed civic guards, and plain-clothed detectives. The police were present in anticipation of protests, but there were none. The team was brought to the Gresham Hotel, where an impromptu press conference took place. The spokesman for Mr. Rato Dugonjic, president of the Yugoslav Football Association, said that they were told of the protests while waiting in London for their flight to Dublin. ‘It is all very difficult,’ he said, as ‘this is the first time this has happened to us and we have travelled to the five continents.’ When asked about the protests and the imprisonment of Cardinal Stepinac, the spokesman replied, ‘we completely ignore these things.’ The Yugoslav ambassador to London, Dr. Vladmir Velebit, was not so reticent. In a statement issued to the Irish Times, he said that it was ‘deplorable’ for the Archbishop to use a soccer match for a ‘campaign of intolerance’, particularly ‘as it comes at a time when racial, ideological and religious prejudices are being overcome in international relations.’ The ambassador and his staff were taken by surprise by the protests, and had considered cancelling the match, but had gone ahead because, in the words of the embassy’s press officer, Mr. Pasic, ’we do not want to let down people who have undertaken this costly venture in good faith.’ The protests were more of a surprise to the Yugoslav embassy because it believed that it had good relations with Ireland, both with the Irish embassy in London and with the Irish ambassador in Rome, whom Dr. Velebit met recently during his tour of duty.

The protests continued. On Tuesday 18 October the Irish and Shelbourne trainer, policeman Dick Hearns, who had been working with the Irish team until Monday, did not turn out with the players. He was replaced by Billy Lord, the Shamrock Rovers’ trainer. When asked why he had withdrawn from the game, Mr. Hearns said ‘I would rather not say.’ Sean Brady, TD, called on Dublin’s workers ‘to deny themselves the pleasure of witnessing a good soccer match as an act of respect for, and sympathy with those brave, distinguished prisoners [in Yugoslavia].’

The decision by Transport F.C. to boycott the game led to speculation that transport workers would follow suit, but a spokesman for the State-run transport company, Córas Iompar Eireann (CIE) said that ‘our football club and our passenger services are two distinct things… and if there is a demand for [extra buses] on Wednesday they will be provided.’ The company also announced that cheap day tickets would be issued from all mainline stations for those attending the game. The FAI said that, despite the protests, there had been a brisk demand for tickets, ‘well up to previous internationals’, and the Dáil and government boycott was broken by Dan Breen TD, who announced his decision to attend the game and ‘to fire his last shot for Ireland.’ Overall, though, the feeling was that public opinion was against the game, and sizeable protests were expected outside Dalymount Park.

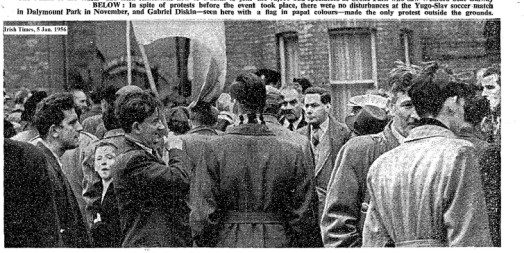

Pre-match speculation on the possible attendance ranged from 5,000 to 35,000, ‘the fixture having aroused such varying degrees of indignation and sympathy.’ In the end, the official figure for attendance was 22,000, although the Irish Times and the Irish Press put the figure at 21,400, with the Press adding that the gate for the game was £4,000. Although there had been talk of a walkout by at least some of the Irish players, this proved to be unfounded, and the team played as named on 12 October. Police and detectives were on duty at the ground, both inside and outside, but there were no incidents. John Cooney, in his biography on McQuaid, wrote that the supporters ‘had to pass a picket of Legion of Mary members carrying anti-communist placards.’ A similar claim is made by Tim Pat Coogan, who wrote that the 21,400 showed up ‘despite having to pass a large picket formed by Catholic actionists.’ The only visible protest on the day, apart from the drop in attendance, came from one man who carried a papal flag as he walked outside the entrance to Dalymount Park. He was named by the Irish Press as Mr. Gabriel Diskin, a Dublin-based journalist. Diskin worked for the Irish Press at the time.

Pre-match speculation on the possible attendance ranged from 5,000 to 35,000, ‘the fixture having aroused such varying degrees of indignation and sympathy.’ In the end, the official figure for attendance was 22,000, although the Irish Times and the Irish Press put the figure at 21,400, with the Press adding that the gate for the game was £4,000. Although there had been talk of a walkout by at least some of the Irish players, this proved to be unfounded, and the team played as named on 12 October. Police and detectives were on duty at the ground, both inside and outside, but there were no incidents. John Cooney, in his biography on McQuaid, wrote that the supporters ‘had to pass a picket of Legion of Mary members carrying anti-communist placards.’ A similar claim is made by Tim Pat Coogan, who wrote that the 21,400 showed up ‘despite having to pass a large picket formed by Catholic actionists.’ The only visible protest on the day, apart from the drop in attendance, came from one man who carried a papal flag as he walked outside the entrance to Dalymount Park. He was named by the Irish Press as Mr. Gabriel Diskin, a Dublin-based journalist. Diskin worked for the Irish Press at the time.

There were cheers for the Yugoslav and Irish players as they made their way onto the pitch. The largest cheer, however, was reserved for Oscar Traynor, a former Belfast Celtic player, who greeted the teams in the absence of the President. The spectators stood for both national anthems, which were played over the public address system in the absence of the Army band. The Yugoslav national anthem had been recorded the previous night by a Dublin band, who used special scores flown in the previous week by the Yugoslav Football Association. There was some confusion at the raising of the Yugoslav flag, when it was pointed out by a Yugoslav official that it was upside-down. It appears to have been an honest mistake, and was soon rectified.

The match ended 4-1 for Yugoslavia, who played, according to the Irish Times journalist, Frank Johnstone, with ‘calculated movements after the manner of a master of chess, carried through with the speed of light.’ Ireland’s only goal came in the 32nd minute, with Yugoslavia already 2-0 up, and was scored by Arthur Fitzsimons (Middlesbrough). Milutinovic, who had scored Yugoslavia’s first two goals, completed a hat-trick just before half-time. The end of the game saw Yugoslavia receive a standing ovation from the crowd, who had just seen Ireland receive its heaviest home defeat since Spain won by the same margin in 1949. After the game, the Yugoslav team and officials were guests of honour at a banquet hosted by the FAI in the Gresham Hotel, and were presented with gifts of Waterford glass, Foxford rugs, and (presumably, empty) wallets. Rato Dugonic told the FAI that ‘our feelings after the wonderful reception we got at today’s match are different from those we had when we arrived and read your newspapers…. [and] I hope this is but the beginning of better understanding between Ireland and Yugoslavia, Irish sportsmen will always be welcome in my country.’ Oscar Traynor praised the Yugoslav team for a wonderful display of skill and sportsmanship. With regard to the controversy surrounding the game, he said that ‘we have nothing to defend. Our actions have been above board, friendly and will continue so.’

The match ended 4-1 for Yugoslavia, who played, according to the Irish Times journalist, Frank Johnstone, with ‘calculated movements after the manner of a master of chess, carried through with the speed of light.’ Ireland’s only goal came in the 32nd minute, with Yugoslavia already 2-0 up, and was scored by Arthur Fitzsimons (Middlesbrough). Milutinovic, who had scored Yugoslavia’s first two goals, completed a hat-trick just before half-time. The end of the game saw Yugoslavia receive a standing ovation from the crowd, who had just seen Ireland receive its heaviest home defeat since Spain won by the same margin in 1949. After the game, the Yugoslav team and officials were guests of honour at a banquet hosted by the FAI in the Gresham Hotel, and were presented with gifts of Waterford glass, Foxford rugs, and (presumably, empty) wallets. Rato Dugonic told the FAI that ‘our feelings after the wonderful reception we got at today’s match are different from those we had when we arrived and read your newspapers…. [and] I hope this is but the beginning of better understanding between Ireland and Yugoslavia, Irish sportsmen will always be welcome in my country.’ Oscar Traynor praised the Yugoslav team for a wonderful display of skill and sportsmanship. With regard to the controversy surrounding the game, he said that ‘we have nothing to defend. Our actions have been above board, friendly and will continue so.’

Mr. Wickham of the FAI was interviewed after the game. He said that he believed the game was well supported, telling the press that “for a mid-week game, a crowd like that is quite good.’ His comments have been taken at face-value, and repeated as a reasonable assessment of the game. When placed in the context of Irish international soccer, however, it appears that he was putting a brave face on things. The controversy lost revenue for the FAI. (A somewhat crude approximation, based on the match gate of £4,000 from or 21,400 supporters, is £1,000 lost for every 5,350 fans that stayed away.) The Yugoslavia experience did not stop Ireland from playing other Eastern-Bloc countries, particularly Poland (1958, 1964), and Czechoslovakia (1959, 1961), but Ireland would not face Yugoslavia again until 1988, when the home team won 2-0 in a friendly at Lansdowne Road.

Conclusion

In 1954 Archbishop Stepinac was visited by an Irish woman named Florence Cullen. He told her, “you are here, you, alone with me. For me, you are the Irish people, so to you I give this blessing for the Irish people, every one of the three million of them.” His trial and subsequent imprisonment had not only made the news in Ireland, but had provided a rallying point for southern conservative Irish society. The Dáil debates, the Mayday rally, and the offering of masses by thousands of ordinary people all point to an Irish certitude that the Archbishop was in the right, and the Yugoslav authorities in the wrong. Archbishop Stepinac was sent messages of support by the Irish Roman Catholic Church and affiliated lay organisations. This was to be expected. However, the trade union movement, local community and business organisations, and, indeed, the entire political and diplomatic establishment, also threw their weight behind the Archbishop. The Ireland-Yugoslavia game took place within the context of such national consensus.

The match, in the end, became a protest, but it was a reluctant one. There were a number of reasons why it went ahead. Both the FAI and Irish Soccer pointed to the necessity of fixtures against quality football opposition in order for the Irish team to develop at international level, and Yugoslavia were one of the top teams in the world. The reputation of the Irish Republic team within FIFA was also an issue. The FAI had already turned down a request by Yugoslavia for a fixture, and by 1955 it felt that no longer could it justify such a position. The main reason, however, was that the Irish soccer fan base wanted to see Yugoslavia play.

The Ireland-Yugoslavia game has entered Dublin folk-memory as the day when the city’s working class, quite literally, roared back at its archbishop. John Cooney, in his biography of McQuaid, wrote that ‘a substantial section of the crowd was composed of non-soccer fans who had decided to register a protest against McQuaid’s campaign.’ It is a conclusion that ignores the level of soccer support in Dublin, and Ireland, in the 1950s. The average Dalymount gate for a game against a team of Yugoslavia’s calibre was 40,000. Furthermore, McQuaid’s comments were hardly out of step with politicians who clashed words over the strength of their “Catholicity” in 1946, or the estimated 40,000 trade unionists and lay church members who protested on Mayday in 1949. The gate for the 1955 game was down, but those who did show up were there to see a world-class team play at a time when such games were comparatively rare. The roar that the Archbishop heard that day was a soccer roar. A neglected aspect of Irish culture revealed itself that day. The support for soccer among working-class Dublin was such that even in the face of such opposition the Yugoslavs got to play in Dalymount – and that is enough significance for any one game.

Interesting that the government was not FF. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Government_of_the_15th_D%C3%A1il and indeed Oscar Traynor mentioned was a senior FFer.